Table of contents

Here is a fun puzzle:

You are given two eggs, and access to a 100-storey tower. Both eggs are identical. The aim is to find out the highest floor from which an egg will not break when dropped out of a window from that floor. If an egg is dropped and does not break, it is undamaged and can be dropped again. However, once an egg is broken, that's it for that egg.

If an egg breaks when dropped from a floor, then it would also have broken from any floor above that. If an egg survives a fall, then it will survive any fall shorter than that.

The question is: What strategy should you adopt to minimize the number egg drops it takes to find the solution? (And what is the worst case for the number of drops it will take?)

Once you solved it for two eggs, can you solve it for three eggs? Can you find a generalized solution when you have a tower with floors and if you have eggs?

If you are interested in an easy to understand intuitive explanation to the egg storey tower problem, check out the following video:

https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/NGtt7GJ1uiM

We will go through this problem for the eggs and eggs variant, and derive the solution mathematically. Then, we will generalize the problem with floors and eggs.

Two eggs

We have eggs to start with and a storey tower to explore.

Let's consider what we would do if we had just one egg.

With just one egg, we could drop the egg from floor . If it breaks, we stop and can definitively say that for any floor and above all eggs would break. If it doesn't break, we can proceed to floor and repeat.

This means that for a tower with floors we will need up to drops to definitively say at which floor the egg would break. The above strategy gives us the minimum number of drops to guarantee that we find at which floor the egg would break. Or in other words, we can search floors with drops. Let's call the lowest floor in the tower at which a egg would break the breaking floor. Here, is the breaking floor and is the highest floor from which an egg will not break. Once we can find the breaking floor, we can find the solution to this puzzle. The aim of this puzzle is to minimize the worst case when trying to guarantee finding the breaking floor.

What could we do differently with eggs?

With eggs, in fact we can explore the search space more efficiently. We can use the first egg to partition the total number of floors, and once the first egg breaks we can use the second egg to search floors within the last partition.

As an example, let's say you decide to drop the first egg from every floor. If it doesn't break at floor , , , or but breaks at floor you can use the second egg to explore floors - . If it finally breaks at floor , you would have used drops of the first egg and drops of the second egg to find the breaking floor.

We can do even better though.

Let's assume that the minimum number of drops required to guarantee finding the breaking floor for a storey tower is . If when we drop the first egg and the egg breaks, we can use drops of the second egg to find the breaking floor. We already know that we can search at most floors with the egg using drops. So if our first drop was from a floor greater than , we would not be able to guarantee finding the solution to this problem. This means that if we have eggs we would want to drop the first egg from floor , where is also the minimum number of drops that will guarantee finding the breaking floor in a storey tower.

When we drop the first egg from floor , if the egg breaks, we can use the second egg to find which floor from to is the solution. If the egg doesn't break, now we have used drop. Let's assume that the first egg breaks on the second drop. When this happens, we can use the remaining egg to explore floors with drops find the breaking floor. With drops, we can search from floor to floor . This means that when we drop the first egg the second time, we should start from , i.e., , to allow for finding the breaking floor.

If the egg doesn't break on the second drop, we have now used drops. If the egg is going to break on the third drop, we have to allow for searching floors with the second egg. This means we should drop the first egg on our third attempt from floor number , i.e., . We can also say that with drops and eggs we are guaranteed to find the floor if it is within the first floors, i.e. floors.

Seeing the pattern here?

For a storey tower, we need to ensure that with drops we cover all the floors of the tower. That gives us this constraint.

Which can be rewritten as:

Or, in closed form as:

We know is in this problem.

This tells us that with drops we can guarantee finding the breaking floor in a tower with up to floors.

Three eggs

We have already previously established the best strategy for egg and eggs.

Let's define some terminology:

where and are the number of floors that can be checked with and eggs respectively with drops.

And we know that can be written as:

So if we have 3 eggs and if the first egg breaks on the first drop, we want to ensure that we can check floors with the remaining drops. That means we should drop the first egg from floor:

For the second drop, we can start from floor:

For the third drop, we can start from floor:

Seeing a pattern emerge again?

Similar to before, the total number of floors we can check is constrained by :

This can be rewritten as:

which results in:

Solving this, we get drops for eggs. With just drops, we can guarantee finding the breaking floor in a storey tower.

eggs

Let's see if we can generalize this for eggs.

With egg and drops, we know we can check floors. Let's define this as , i.e.:

[]{#eq-f_x_1}

where is the floors that can be checked with drops and eggs.

We can safely say that with drops or eggs we can check floors.

So we can write Equation 1{.quarto-xref} as the following:

For eggs and drops, the number of floors we can check, i.e. , is:

[]{#eq-f_x_2}

We can expand this as the following:

and substitute in Equation 1{.quarto-xref} to get:

And, for eggs and drops, the number of floors we can check, i.e. , is:

Again, we can expand it and rearrange some terms:

and substitute in Equation 2{.quarto-xref} to get:

We can see a pattern emerging here. The generalized equation can be written like so:

[]{#eq-f_x_n}

This is also known as a recurrence relation.

This result can be reasoned through intuition as well. To find the total floors you can check with eggs and drops, it will be (your first drop) plus the maximum number of floors you can check with eggs and eggs (if the first egg does not break) plus the maximum number of floors you can check with eggs with eggs (if the first egg does break).

If we wanted to, we could expand this recurrence relation1.

Here is the expansion increasing the depth in the direction of number of drops:

Eagle eye readers will notice a pattern.

It turns out that this expansion is related to the binomial coefficients.

If we had infinite number of eggs, you'd see that the first element is the only term that contributes to , since the others will be for where is the depth in the triangle. That is to say, if we had infinite eggs, with 6 drops we can guarantee checking 63 floors.

Using this, we can say that, with drops we can guarantee checking floors if we had infinite eggs2.

Implementation

Let's implement this problem.

julia> println(VERSION)1.4.0We can implement Equation 3{.quarto-xref} as a function:

julia> f(x, n) = x == 0 || n == 0 ? 0 : 1 + f(x - 1, n) + f(x - 1, n - 1)f (generic function with 1 method)For egg, the number of floors you can check is the number of drops you make.

julia> arr = 1:100;

julia> @test f.(arr, 1) == arrTest PassedAnd, we can verify that it works for eggs as well.

julia> @test f(14, 2) >= 100Test Passed

julia> @test f(14, 2) == 105Test PassedWe can implement this generally like so:

julia> function starting_floor(floors, n) for x in 1:floors if f(x, n) >= floors return x end end endstarting_floor (generic function with 1 method)And get the answer to the problem programmatically.

julia> starting_floor(100, 2)14Using the function f, we can also generate a table that explores what

is the maximum number of floors that can be check for various number of

drops and eggs.

| Drops | 1 egg | 2 eggs | 3 eggs | 4 eggs | 5 eggs | 6 eggs | 7 eggs | 8 eggs | 9 eggs | 10 eggs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 drop | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 drops | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 drops | 3 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| 4 drops | 4 | 10 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| 5 drops | 5 | 15 | 25 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| 6 drops | 6 | 21 | 41 | 56 | 62 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 | 63 |

| 7 drops | 7 | 28 | 63 | 98 | 119 | 126 | 127 | 127 | 127 | 127 |

| 8 drops | 8 | 36 | 92 | 162 | 218 | 246 | 254 | 255 | 255 | 255 |

| 9 drops | 9 | 45 | 129 | 255 | 381 | 465 | 501 | 510 | 511 | 511 |

| 10 drops | 10 | 55 | 175 | 385 | 637 | 847 | 967 | 1012 | 1022 | 1023 |

| 11 drops | 11 | 66 | 231 | 561 | 1023 | 1485 | 1815 | 1980 | 2035 | 2046 |

| 12 drops | 12 | 78 | 298 | 793 | 1585 | 2509 | 3301 | 3796 | 4016 | 4082 |

| 13 drops | 13 | 91 | 377 | 1092 | 2379 | 4095 | 5811 | 7098 | 7813 | 8099 |

| 14 drops | 14 | 105 | 469 | 1470 | 3472 | 6475 | 9907 | 12910 | 14912 | 15913 |

| 15 drops | 15 | 120 | 575 | 1940 | 4943 | 9948 | 16383 | 22818 | 27823 | 30826 |

Maximum number of floors that can be checked with drops and eggs.

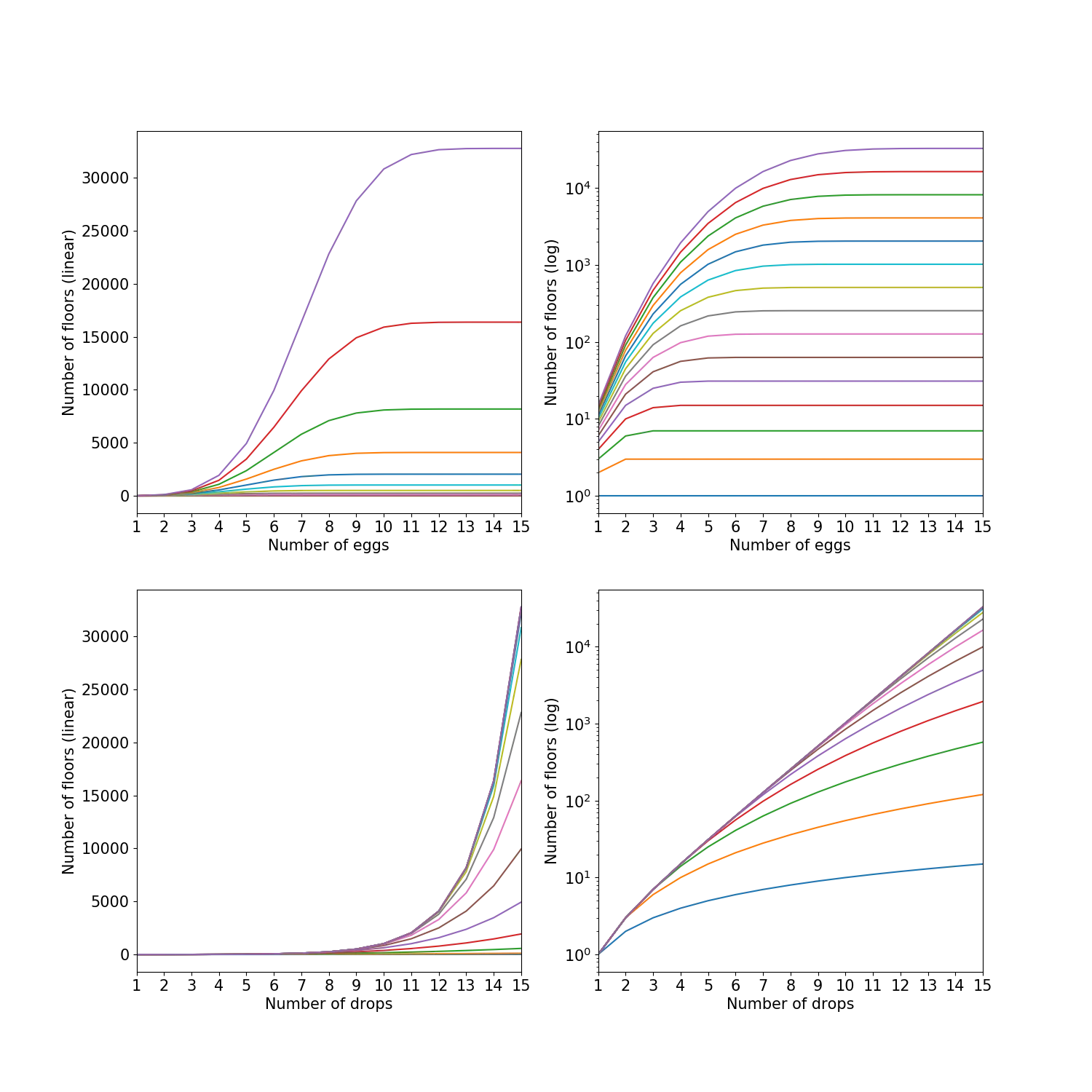

You'll notice that the upper right corner of the table stays the same if you increase the number of eggs you have at your disposal. You can see this even more clearly in this visualization.

There's a minimal number of drops required to guarantee that you will find the breaking floor, even if you have unlimited eggs.

If you want to check floors, as long as you have more than eggs, you can have to use a minimum of 3 drops to guarantee finding the breaking floor.

For 100 floors, it is drops. If you had unlimited eggs, you would use the largest partition possible. That means dividing the total floors by .

Partitioning the floors equally or in other words bisecting the floors, and exploring the partition of interest using the same strategy is the most efficient way of finding the breaking floor.

So there you go! We have solved the general case for the egg and tower puzzle.

Footnotes

-

Thanks to /u/possiblywrong for pointing this out. ↩

-

If we had a finite number of eggs, an approximation of this recurrence can be made. See /u/mark_ovchain's insightful comment on this thread for more information. ↩